Publication

Article

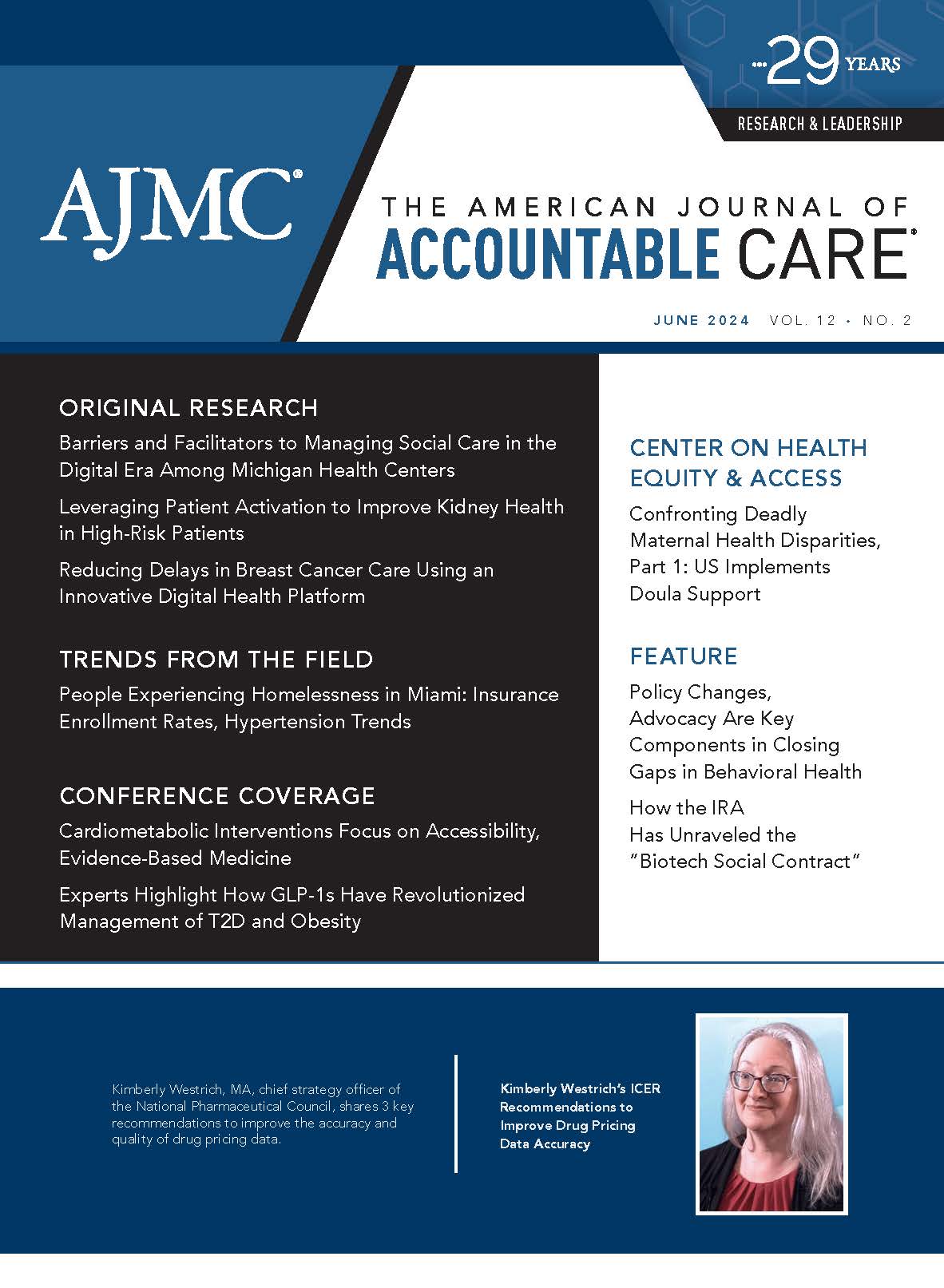

How the IRA Has Unraveled the “Biotech Social Contract”

Author(s):

At a symposium on the impact of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) on pharmaceutical innovation and access, speakers urged the audience to join in advocating for changes to the law.

The American Journal of Accountable Care. 2024;12(2):57-60. https://doi.org/10.37765/ajac.2024.89575

There’s nothing wrong with trying to help consumers pay less out of pocket for drugs. But how you do this matters, and too many parts of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) do little for consumers while doing a lot to harm the biotech industry that has saved lives, according to experts who gathered in Newark, New Jersey, for an April 18, 2024, symposium on the impact of the 2022 law.

“Innovation and Patient Access After the Inflation Reduction Act” drew 100 attendees from the biopharmaceutical industry and Rutgers Business School, which is celebrating the 20th year of the Blanche and Irwin Lerner Center for the Study of Pharmaceutical Management Issues, named for the former Hoffman-LaRoche chair and his wife. Roche alum Paul Hastings, now president and CEO of Nkarta Therapeutics, gave a lively keynote address, which was followed by a dynamic panel discussion led by Richard H. Bagger, JD, a former executive vice president of Celgene and current adjunct faculty member at Rutgers University’s Eagleton Institute of Politics.

By his own account, Hastings defies labels. He is both “openly gay and liberal” on social issues, advocating to end gun violence and for LGBTQ employees to have full health care access, and fiscally conservative on business matters. He grew up modestly in Portland, Maine, and he’s had Crohn disease since he was a young adult, which gives him a patient’s perspective.

And make no mistake: “I do not support the Inflation Reduction Act,” he said.

The wide-ranging IRA was projected by the Congressional Budget Office to reduce the federal deficit by $237 billion over 10 years through 2031.1 It has multiple components that affect Medicare Parts B and D and the pharmaceutical industry, including caps on out-of-pocket costs and a provision that requires drugmakers to pay rebates to the government if prices paid for drugs used by Medicare beneficiaries rise faster than the rate of inflation.1

In Hastings’ view, the IRA dismantles the framework of fairness created 40 years ago in the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act—better known as the Hatch-Waxman Act—which created clear, predictable timetables when biotech companies had exclusivity for their drugs and a generic manufacturer could challenge patents in court.2

“You get a period of exclusivity to sell your drugs, and then they go off patent—they become generic,” Hastings said, noting that 80% of the drugs prescribed today are generic.3 “If you follow what I call the biotech social contract and you actually let your drug [go] off patent…you should have…figured out what the next innovation is so we can partake in that innovation again.”

In the case of Nkarta, which develops therapies based on natural killer cells,4 that would mean accepting that a biosimilar is going to be part of the picture after patent expiration. “That’s what I call the cycle of life in the biotech social contract,” Hastings said.

The trouble with the IRA, Hastings said, is that it shatters the life cycle that fuels biotech innovation while doing nothing about abuses by pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), which he said create incentives to raise drug prices, not lower them.

The IRA, he said, contains provisions that will discourage investment or create an unlevel playing field, including as follows:

- If manufacturers selected to negotiate with CMS do not enter into drug pricing agreements, they face excise taxes of up to 95% of a drug’s revenue.5

- The IRA spares biologics from price negotiation for 13 years but protects small molecules for only 9 years,1 which both Hastings and a panelist said would discourage investment in small molecules.

- The law discourages companies from finding additional indications for drugs, which is bad news for patients with rare diseases.

Hastings did not specifically endorse parts of the IRA that cap seniors’ out-of-pocket costs for Medicare Part D at $2000 a year or allow deductibles to be evenly spread throughout the year, but he did discuss affordability. “Their out-of-pocket costs are what is getting in the way—not what we charge insurance companies. It’s what they pull out of their pocket to give to the pharmacist,” he said. “That gets lost in this whole discussion.”

Rebates that pharmaceutical companies pay to PBMs to ensure formulary placement need to be redirected, he said. “I can spend hours talking about who should be taking those rebates—instead of providing those rebates back to employers, [we] should be giving those rebates to patients to get their out-of-pocket cost down to zero.… Nobody fakes being sick. Why do they need to be disincentivized to take the drug by pulling money out of their pocket because they have a serious disease? Those are things that should be fixed.”

Congress is realizing that PBMs “don’t do anything,” he said. “They’re supposed to help us have lower prices, but they take the rebate that they get from us, which they negotiate almost as hard as CMS negotiates. And the higher our prices, the happier they are, because their rebate is more. They have no incentive to lower drug prices.”

Hastings’ specific pitch to the Rutgers audience was to join in advocating for changes to the IRA, during what is expected to be a historic lame-duck session of Congress after the November 2024 election.

The Biden administration is already looking to expand the number of drugs subject to negotiation,6 and early reports from the US District Court in Trenton, New Jersey, where the industry is challenging parts of the law, suggest an uphill battle.7 Thus, Hastings said, the IRA itself must be amended, both to ensure innovation in the future and to protect an industry that, by design, will have many failures for every blockbuster.

Drug development takes time, he said, and both companies and innovators themselves need time to breathe between the hits. “You have to fail before you succeed. That’s a tenet of our industry. One out of 10 drugs will make it. So if you don’t have this continual access to innovation and you shut things down, just because 1 thing went bad, you’re going to miss that 10th thing.”

Creating a healthy environment for innovation has led to the development of many biotech clusters with high-paying jobs and spin-off benefits to the surrounding community, he said. (In New Jersey, where the symposium took place, 14 of the top 20 pharma companies have a presence and 65,000 individuals work directly in the industry.8)

But this message requires constant reminders to members of Congress, Hastings said. “If we’re not there, someone else is going to be there. And some PBM is going to be telling everybody how evil we are.

“Because it’s a fight,” he said.

Will the IRA Lead to Reduced Access for Patients?

During the discussion that followed, Bagger and 3 panelists dug into details of the law and predicted unintended consequences—from higher prices when drugs enter the market to delayed launches as companies explore all possible uses to the possibility that negotiating with Medicare could make some drugs less accessible to patients.

Joining Bagger for the discussion were as follows:

- John M. O’Brien, PharmD, MPH, president and CEO, National Pharmaceutical Council (NPC);

- Neal Masia, PhD, cofounder and CEO, EntityRisk, and adjunct professor, Columbia University; and

- Amadou Diarra, PhD, former senior vice president, global policy, patient advocacy & government affairs, Bristol Myers Squibb.

Bagger examined the fallout of several IRA provisions, including as follows:

- The law requires rebates if drug prices exceed the urban Consumer Price Index (CPI-U); it spells out which Part B drugs are included, and nearly all Part D drugs are factored into the calculation.

- Restructuring under Part D to avoid the “donut hole” now shifts more costs onto the high-priced specialty pharma drugs that reach the catastrophic level faster.

- Under the current law, Medicare is negotiating the first 10 drugs but will eventually negotiate 100 drugs, including some Part B drugs. Critics have noted that the law fails to account for rebates that pharmaceutical companies pay to PBMs or how this affects prices.

“All of these have impacts on what’s happening in real time, with respect to investment decisions that are being made about drug development, portfolio management, etc,” Bagger said.

O’Brien said he’s concerned about the speed with which the IRA is being implemented. Although politics is always part of the background, “that calendar, unfortunately, is largely going to be influenced by political decisions,” he said.

It’s not clear how CMS is making its decisions, O’Brien said, nor is it clear how the process will affect formulary placement or clinical decisions once the process is over.

“Are you going to choose a therapeutic alternative in the same category and class as the selected drug that you’re going to set the price for? Are you going to choose a generic? Or are you going to choose a drug that physicians haven’t been comfortable using since the days of sword fighting?” he asked.

Companies will have to submit their dossier for the second round of drug negotiations before it’s clear which factors CMS weighed in the first round, he noted. “I’ve seen nothing and have very little confidence that we’re going to get a transparent, predictable, evidence-based process,” he said.

Bagger asked for comments about the IRA’s effects on life cycle management and launch strategy, and Masia said the irony is that an act that has “inflation reduction” in its name may push drug prices up. Historically, Masia said, drugs launched at a lower price as the manufacturer gathered evidence. “As time accumulates, you’ll match the price to what the market tells you,” he said.

But the CPI-U provisions mean that companies may want to launch at the highest possible price, even holding back a launch until they know more about all the populations that might benefit as going for new indications later might be off the table.

“You’re very limited on your list price increases forever [from] the day you launch,” he said.

O’Brien noted that results of the NPC’s research, published in The American Journal of Managed Care®,9 show that indications on existing drugs are the rule rather than the exception. “If you look at the top 50 drugs in Part D by gross spending, as Neal talked about, 33 of them fall into that category of having subsequent indications,” he said. “If you started your work on your next indication before your first approval, you’re lucky to get that second approval in about 2 years.” More typically, a second approval takes approximately 7 years, he said.

“We believe that the IRA is going to decrease the number of subsequent indications or potentially delay launches, which no company wants to admit,” O’Brien said. The IRA could also cut incentives for outcomes studies that show a drug helps patients live longer or have fewer cardiovascular events.

“Those studies are really important to helping clinicians decide how to practice and inform evidence-based guidance,” he said. “We think this law has a real potential to delay launches, reduce a number of subsequent indications, and really have a chilling effect on evidence generation that clinicians rely on.”

Diarra noted that the US has one of the highest total health expenditures in the world, at 16.6%, of which 15% comes from spending on pharmaceuticals. In theory, because health equals wealth, we should all be happy that the more government spends on health care, the more people are healthy and the more wealth results. “The reality is more complex,” he said.

Cutting pharmaceutical prices may seem like an easy lift politically compared with other choices, such as cutting military spending, but the pharmaceutical industry reinvests 30% of its capital, which is something Diarra said might not continue. Right now, US leaders may take for granted that their citizens have near-universal access to approved medications—the rate is 96%. The next closest country is Germany, at 74%, Diarra said.

What happens, O’Brien asked, if access to drugs tightens for patients? If nothing is done to rein in PBMs, a competitor could offer a steep rebate to supplant one or more of the drugs subject to Medicare negotiations required to be offered to plans at “maximum fair price.” As it stands now, these replacements could happen even if the drugs subject to negotiation have stronger evidence and more indications, he said.

In fact, the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 class offers an example, with 2 therapies (empagliflozin [Jardiance] and dapagliflozin [Farxiga]) on the initial list of 10 negotiated drugs,10 whereas others in the class remain outside negotiations. Empagliflozin and dapagliflozin were initially approved to treat type 2 diabetes; the FDA required their manufacturers to conduct cardiovascular outcomes trials that showed benefits in heart failure and preservation of kidney function, leading to additional indications.11

“There is a question as to whether access is going to be maintained,” O’Brien said. “What if there are other drugs in the same therapeutic class that are still willing to pay a rebate? [If] I’m a Part D plan, I’d have picked up 4 times the risk. And with [changes to] the catastrophic phase, there’s a financial incentive for me to restrict access to a drug with a maximum fair price, and instead prefer or favor a drug in which I can still generate a rebate.”

There are already data circulating among health plans, he said, that suggest “‘we’re not so sure that the selected drugs might be where we want to start.” He added, “So whether or not this lowers patient out-of-pocket costs, aside from the out-of-pocket cap, and the smoothing—which is a good thing—whether or not this increases access, those are open questions to me, based on how the channel responds.”

Author Information: Ms Caffrey is an employee of MJH Life Sciences®, parent company of the publisher of The American Journal of Accountable Care®.

REFERENCES

- Cubanski J, Neuman T, Freed M. Explaining the prescription drug provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act. KFF. January 24, 2023. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/explaining-the-prescription-drug-provisions-in-the-inflation-reduction-act/

- The Hatch-Waxman Act: a primer. EveryCRSReport.com.

September 28, 2016. Accessed May 1, 2024.

https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/R44643.html - Buying into generic drugs. Harvard Health. July 15, 2016. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/buying-generic-drugs-201607159982

- Nkarta. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://www.nkartatx.com/

- Castronuovo C. Lawsuits, tax fuel doubt as Medicare preps drug pricing talks. Bloomberg Law. August 25, 2023. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://news.bloomberglaw.com/health-law-and-business/lawsuits-tax-fuel-doubt-as-medicare-preps-drug-pricing-talks

- Gardner L, Lim D. Biden asks to expand Medicare drug price negotiations. Politico. March 8, 2024. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://www.politico.com/newsletters/prescription-pulse/2024/03/08/biden-asks-to-expand-medicare-drug-price-negotiations-00145830

- Pierson B. J&J, Bristol Myers lose challenges to US drug price negotiation program. Reuters. April 29, 2024. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://www.reuters.com/legal/jj-bristol-myers-lose-challenges-us-drug-price-negotiation-program-2024-04-29/

- Carpenter F. The top 6 pharmaceutical companies in New Jersey. Biospace. September 23, 2022. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://www.biospace.com/article/top-9-biotech-giants-to-work-for-in-new-jersey-/

- Patterson J, Motyka J, O’Brien JM. Unintended consequences of the Inflation Reduction Act: clinical development toward subsequent indications. Am J Manag Care. 2024;30(2):82-86. doi:10.37765/ajmc.2024.89495

- HHS selects the first drugs for Medicare drug price negotiation. News release. HHS; August 29, 2023. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2023/08/29/hhs-selects-the-first-drugs-for-medicare-drug-price-negotiation.html

- Padda IS, Mahtani AU, Parmar M. Sodium-glucose transport protein 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors. StatPearls. June 3, 2023. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK576405/

2 Commerce Drive

Suite 100

Cranbury, NJ 08512

© 2024 MJH Life Sciences® and AJMC®.

All rights reserved.