- August 2021

- Volume 27

- Issue 6

Genomic Testing Creates Opportunities for Collaboration Between Academic Centers, Private Sector

In recent years, genomic testing has changed the face of cancer care, as it helps ensure more informed decision-making between doctor and patient in cancer care. But precision medicine solutions cannot be delivered equitably if some patients lack access to testing, or if tests results are used incorrectly.

A June 2, 2021, webinar from Oncology Value Coalition, a series presented by The American Journal of Managed Care® (AJMC®), featured experts from City of Hope National Medical Center, of Duarte, California, and AccessHope LLC, which delivers cancer care to employers and their health care partners. The panel also featured a representative from Highmark Blue Cross Blue Shield, the integrated delivery network based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Serving as moderator was Joseph Alvarnas, MD, vice president for government affairs and chief clinical adviser for AccessHope. Alvarnas is also a clinical professor in the Department of Hematology & Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation at City of Hope and editor-in-chief of AJMC®’s Evidence-Based Oncology™.

Joining Alvarnas were:

• Afsaneh Barzi, MD, PhD; medical director, gastrointestinal oncology, AccessHope; director, employer strategy, associate clinical professor, Department of Medical Oncology and Therapeutics Research, City of Hope

• Sameera Rahman, MD; senior medical director, Highmark Inc

• Howard (Jack) West, MD; executive medical director, AccessHope; associate clinical professor, Department of Medical Oncology and Therapeutics Research, City of Hope

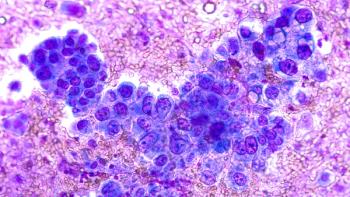

The Rise of Precision Medicine

Alvarnas explained that in the early 1950s and 1960s, cancer investigators “finally appreciated that cancer could, in fact, carry nonrandom genetic mutations.” The breakthrough discovery was the Philadelphia chromosome; at first, a broken chromosome was seen as a way to confirm diagnosis, but soon came the knowledge that the mutations were therapeutic targets that could change the course of treatment.1 Chronic myeloid leukemia was the first huge success story; in the past, patients faced a median survival of 3 years, and only 20% had an allogenic donor for stem cell transplantation. The arrival of tyrosine kinase inhibitors, specifically imatinib (Gleevec), turned chronic myeloid leukemia into a chronic disease.

“We now move to a future where a vast majority of patients do very well, simply taking a pill a day,” Alvarnas said. “What we previously referred to as magic bullets become a new reality. And when we look at other diseases, the application of genomic testing and more effective therapeutic risk stratification and alignment of therapeutics has profoundly changed cancer prognosis.”

The American Cancer Society has seen the biggest drops in cancer mortality in the past 2 years.2 “To think about it another way, there’s a life dividend that’s coming about as a result of more people surviving cancer,” Alvarnas said.

At the same time, the price of genomic testing has dropped, allowing testing to become more accessible, he said. “So, this conversation regarding precision medicine isn’t just an abstract one.”

Each panelist offered a brief introduction, with West explaining that as a thoracic oncologist, he’s seen the shift as investigators saw how EGFR mutations “really trumped clinical factors and were far more important. That was a sea change. And over the last decade or so, we’ve added greatly beyond EGFR to about 9 or so total mutations.” The field shifts every 6 to 12 months, as new market and targeted therapy joins the arsenal, offering fewer adverse effects.

“Now we have the challenge of all of these great markers, but they’re only valuable if you find them, or if you’re looking for them,” West said. “And I think that’s one of the biggest challenges

we face.”

What Cancers Are Affected by Genomic Testing?

Alvarnas then asked the group to discuss where genomic testing had made the biggest mark. West said lung cancer has seen major treatment changes due to testing, but it’s not across the board. While he still sees many smokers who have a driver mutations, the bigger impact has been among patients with “nonsquamous [disease], especially adenocarcinomas,” including patients who never smoked. These patients are likely to be younger, with cancers that are less likely to be associated with the cumulative effects of a lifetime of damage.

Beyond lung cancer, West said, genomic testing applies to many cancers, “especially those where there is not a clear environmental component, and it seems to be a random genetic event.” The ability to generate large increases in survival, “with lock and key” therapeutic regimens that can target exactly the right patients, means that those who are a good match will find their way to the trial, West said, even if travel is required. “It changes the value equation for potential candidates for these trials. And it makes it possible for us to do trials in these narrower populations.”

Barzi said she has always been “fascinated” that many discoveries have occurred by accident, including many treatments that were retrospectively discovered to only benefit that patients with EGFR mutations. “It allows us to recognize that the population of cancer we have is very heterogeneous,” she said. “And biomarkers are perhaps the only way to bring homogeneous populations together, to identify their values and give them treatment.”

What’s clear from basket trials that are not histology specific, she said, is that changing trial designs has allowed opportunities for patients with rare cancers to gain access to trials. That said, Barzi noted that factors in the tumor microenvironment mean “that having the same genomic alteration may not result in the same benefit,” with breast cancer drug development offering a strong example.

“We need to look at the biomarkers we need to find homogeneous populations,” Barzi said. “And the next question is, well, how do we test for biomarkers in a uniform way? And that brings us to what testing we should use?

According to National Institutes of Health data, she said, “the number of diseases that can have genetic testing is rising exponentially,” and the same goes for the number of testing companies and the number of tests themselves. It can be confusing for the local provider who does not see many patients with a given type of cancer, especially when it comes to interpreting results.

“We have come to the age that we have a revolution in realizing the value of genomic and precision medicine. We changed how we design trials. But to make it happen in the population,” Barzi said, “we’ve got to think about the infrastructure of care delivery, which is our providers and our payers. How do we do that?”

The Payer Perspective

Alvarnas then turned to Rahman, asking how payers and employers can gain from the scientific advances—and how do they navigate all the incoming evidence?

“The complexity of care seems to increase over time,” Rahman said. “At the same time, we have a lot of disease states that are eligible for this type of testing. Now, from a payer perspective, I can say that we are always very passionate about making sure that we’re embracing evidence-based care based on guidelines, how we’re always creating evidence-based medical policies and putting in evidence-based care models.”

Patients, she said, don’t understand how pathways work and rely on decisions by physicians for what treatments offer the best value. Payers want to understand what tests will offer that value, and how they can leverage data developed during clinical trials to gain insights. Highmark is using a clinician-led task force to design and develop its own medical policies and oncology care models, “so that we can provide the most clinically effective and highly quality care that’s aligned with the evolution of the space.”

The Changing Therapeutic Pipeline

Barzi said that the arrival of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy has been a game-changer, given the requirements for T-cell collection and a customized engineering process. “It is not a drug that can be given with a schedule—it requires an infrastructure,” she said. This is not something that existing in CMS’ Oncology Care Model in the community oncology practice—and these practices could not deliver CAR T-cell therapy when it was first developed. West said the same was true of running clinical trials. Decades ago, drug trials were conducted in “a completely unselected population, and got pretty poor results most of the time, even when we had successes.”

Enter targeted therapies, and suddenly the math makes trials more cost effective, West said, because it no means treating 100 patients to see 10 successes. Using checkpoint inhibitors for patients who have high PD-L1, but for those with low PD-L1, for example, means response rates will be much higher. Newer agents being used in a targeted manner are seeing response rates of 50% to 60%, whereas if they were used indiscriminately as in prior years, the response rates would be closer to 10%.

“But it is all predicated on getting detailed molecular testing, so that we can not only ask questions today, but have the have the data to look back retrospectively and start asking the smartest

questions for things we don’t understand today,” West said, “As we aggregate enough data, we can

figure out why certain patients with this mutation responded to a targeted therapy, but others don’t.”

While this is good news, it presents challenges. Alvarnas noted that with the number of therapies

reaching the market, and the number in the pipeline, the process of connecting patients with the therapy that matches their cancer takes time that many do not have. “How do you grapple with the complexity of that in order to ensure that this pipeline finds its ability to get into the right people at the right time at the right place without unnecessary delays?”

Highmark’s Rahman said this is where a shift from traditional “utilization management” is needed. When it comes to innovation like CAR T-cell therapy, accessibility is a big issue, and health plans will need to work with physicians as “health care delivery partners,” to make sure that patients get the care they need without adding new administrative burdens. To achieve this, she said, “We have made sure that the health care delivery partners that we work with very closely have implemented certain care models in place.” When it comes to a treatment such as CAR T-cell therapy, “It’s not just the complexity in terms of like the services being rendered that adds to the member experience. But we’re also looking at the physician experience, and we’re thinking about what are some normal types of reimbursement methodologies that we can put into place, so that the provider experience can be improved.

“I think there’s more to come in the next 5 years,” Rahman said.

Barzi said this is where partnerships like AccessHope can make a difference. With AccessHope—which now includes City of Hope, Northwestern, and most recently, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute3—there is real-time decision support for oncologists that offers reassurance for patients, providers, and payers. “It’s an excellent solution to not only help the patients get the right thing, but help the oncologist be reassured that they are giving the right thing.”

Ensuring Access to the Best Care

Alvarnas then turned to one of the most challenging topics in cancer care today: the fact that scientific advances are not reaching everyone. He referenced a report from the American Association of Cancer Research that found significant disparities in care by race, socioeconomic status, and geography.4 Even in wealthy states such as California, the divide exists. One study, he said, “showed less than half of cancer patients in the state got [National Comprehensive

Cancer Network] guideline concordant therapy, and an independent risk factor for not getting

concordant care was being a beneficiary of the state Medicaid program.”

AccessHope was created to address the issue of giving people in all parts of the country access to

subspecialist care regardless of where they live. As West explained, serves are offered, “largely as an

employee benefit” and the number of companies participating has grown steadily.”

With the rise of providers taking on more risk—and employers seeking the benefits of risk-based

contracting, it’s a concept that makes sense when the price of making the wrong decision could be

very large. “For complex cases, with potentially high impact based on just on the risk of the cost of the therapies, the risk of the magnitude of difference between treatments that might be done in the best treatments that could be done,” West explained. “And, and so using this automated trigger list can help identify patients most likely to benefit from having a subspecialist review the case records and offer thoughts to the local team, and work in concert with the local oncologist to deliver the best care where the patient is.”

In most cases, patients don’t have to travel to get treatments; AccessHope can work with the local

oncology team. “This also includes discussion of potentially attractive clinical trials that could be

available in that clinical setting and potentially in that area,” West said.

With the pandemic, the ability to not travel for the best care has been attractive. Moving forward,

West said, “It’s going to be very appealing to work with payers so that it’s not all based on employee benefits, but can be more broadly available to many, many patients and in different geographies.”

Alvarnas noted that this concept fundamentally changes the traditional relationship between community oncologists and the academic centers. The use of telehealth during the pandemic opened everyone’s eyes to the opportunities that were available, Barzi said, especially as a partner with the local provider. “We have come to the realization that virtual care when the doctor is not in direct contact with the patient, could potentially be as good for many conditions, we really don’t need to see or touch our patients to deliver the care,” she said.

Do payers see partnerships as a way to ensure all patients get the best care? Rahman said as data show that only 5% of patients get care that conforms with NCCN guidelines, “it’s clearly concerning.”

The pandemic has awakened the entire health care landscape to how technology can be leveraged

to better connect with patients, and payers see technology as a tool to “nudge members toward the right pathways that are associated with much higher clinically favorable outcomes.” Certainly, in the next 3 to 5 years, she said, payers will be making greater use of technology to ensure members are receiving evidence-based care.

Virtual Care: Pick the Right Setting

West said the use of virtual care in oncology is not appropriate in every setting. “You can’t do a good physical exam,” he said. “And arguably, people would prefer to have their more emotional discussions in a live setting.”

But for other uses, including routine management, virtual care can save patients a long drive to a

cancer center. If it can be used to reduce disparities in access to subspecialty care needed in the age of precision medicine, it merits consideration.

“Telemedicine is a tool that we are just beginning to get a sense of how we might best use it, and I

think it’s not going to replace live visits, but it can be used alongside of them,” West said. “And it has a great role that can really improve how we do care by distributing expertise across the geography far more than we can do with people driving to one center.”

References

1. Nowell PC. Discovery of the Philadelphia chromosome: a personal perspective. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(8):2033-2035. doi:10.1172/JCI31771

2. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA: Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(1):7-33. doi:10.3322/caac.21654

3. AccessHope and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute announce foundational partnership, extending access to cancer expertise across the United States. News release. AccessHope website. June 29, 2021. Accessed July 24, 2021. https://www.myaccesshope.org/press-releases/accesshope-dana-

farber-announce-foundational-partnership

4. Sengupta R, Honey K. AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2020: achieving the bold vision of health equity for racial and ethnic minorities and other underserved populations. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2020;29(10):1843. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-20-0269

Articles in this issue

over 4 years ago

August 2021: Targeted Therapy & Immuno-Oncologyover 4 years ago

ASCO, COA Release Updated Standards for Oncology Medical HomeNewsletter

Stay ahead of policy, cost, and value—subscribe to AJMC for expert insights at the intersection of clinical care and health economics.